Papers, Please

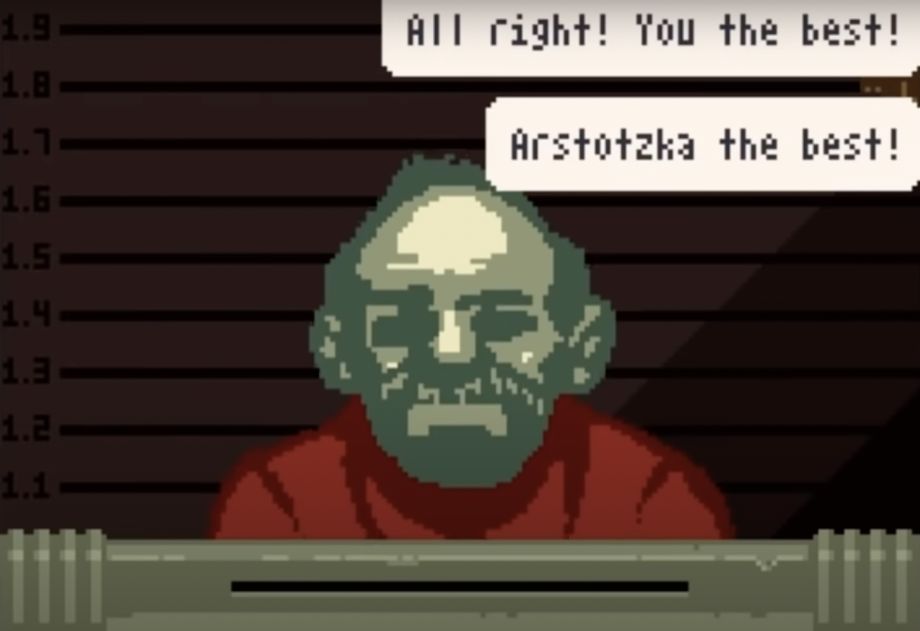

In Papers, Please (2013), developed by Lucas Pope, the user interface is a prime example of diegetic UI, where the interface elements are embedded directly within the game world and are perceptible to the player character. As the player assumes the role of a border checkpoint inspector in the fictional dystopian country of Arstotzka, the entire interface is situated on the inspector’s in-game desk. This spatial diegesis ensures that all interactive elements—passports, entry permits, rulebooks, and stamps—are part of the narrative environment, fostering high narrative immersion and environmental storytelling.

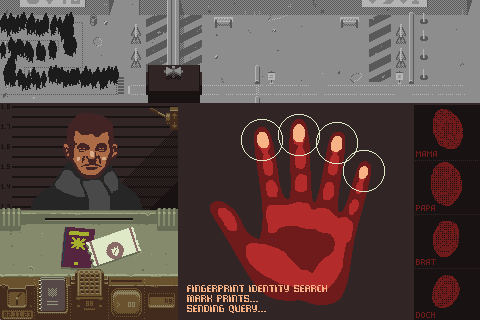

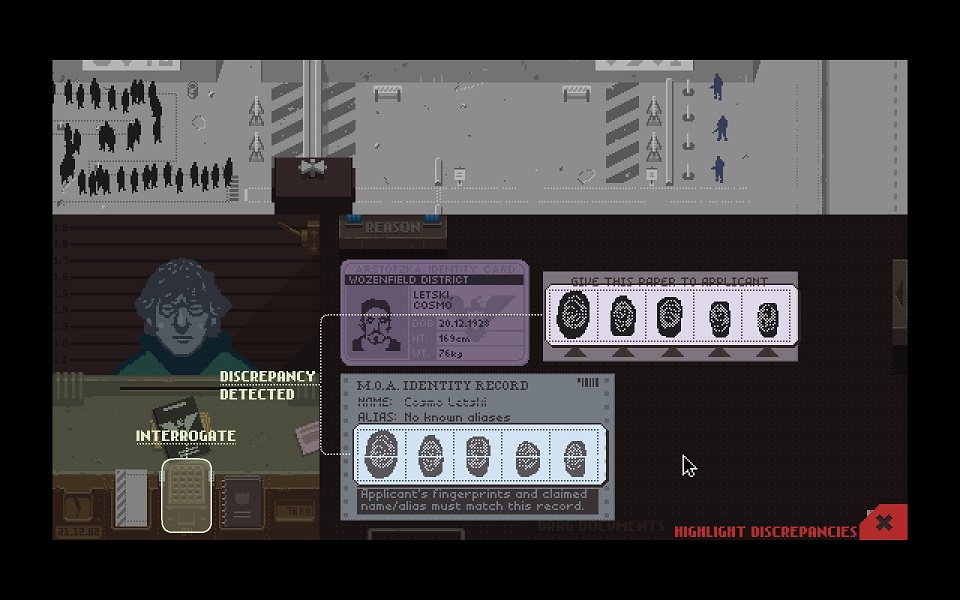

The player manually manipulates documents with a cursor, simulating hand movements, which emphasizes tactile interaction and cognitive load management, as the player must physically compare document data to detect inconsistencies. Tools such as the inspection scanner, rulebook, and audio transcripts are all accessed within this in-world space, reinforcing a single-plane UI design that avoids traditional HUD overlays. By embedding all interface components into the game’s narrative structure, Papers, Please crafts a deeply immersive and oppressive atmosphere that mirrors the bureaucratic monotony and moral tension of the protagonist’s job. This diegetic approach not only reinforces the game’s theme but also elevates the player-character alignment, making the act of interface interaction a form of roleplay rather than mere gameplay mechanics.

Papers, Please uses diegetic UI to fully embed game systems within the protagonist's experience as an immigration officer in Arstotzka. The inspection booth serves as the interface, with passports, permits, and rulebooks handled in real-time on a physical desk. This design turns UI interactions into gameplay, immersing players in the procedural weight and routine of the job.

Papers, Please communicates urgency and stress through physical cues rather than abstract meters. Mistakes are represented by printed citation slips, and time pressure is felt through long lines of applicants. Clunky, manual interactions—like stamping and document checks—intentionally create friction, mirroring bureaucratic pressures and embedding consequences directly into the gameplay.

In Papers, Please, the diegetic interface is integral to its moral and mechanical depth. All decisions—approving bribes, denying refugees—are physically enacted at the player's desk, with consequences playing out in real-time. Booth upgrades are tangible in-world changes, not abstract UI improvements, deepening the sense of complicity and reinforcing the game's themes of bureaucracy and moral conflict.